History of the North Sea cuisine

Join us on a historic food journey by the North Sea.

| The area stretches from Vedersø Klit in the north to Skallingen in the south. Here, you will come across regional fish dishes because of the proximity to the North Sea - for example, dabs. However, the North Sea cuisine is influenced by more than the natural surroundings and it is also about more than local produce and meals - the art of cooking and the tough residents of this region have also had an impact on it. |

Changeable and powerful nature

Few landscapes have changed like the one in western Jutland. The landscape has been changed by waves, storms, sand-filled meltwater rivers and human hands. All of them have reshaped the landscapes, the soils and the fjords where the raw materials live and grow and get their flavour from. The taste begins in nature. The west wind allows fish to be dried directly in the open air. Wind is an important resource. The heath and dunes are important sources of fodder as well. Both the landscapes and elements of nature have shaped the taste of North Sea cuisine.

Photo:VisitVesterhavet

When the glaciers melted about 10,000 years ago, the meltwater rivers pulled sand and gravel with them westwards. This sand and gravel settled like a blanket over the uneven landscapes of western Jutland. The south-western areas were the only parts of Scandinavia that were not crushed under the glaciers. This is still evident today, which is why western Jutland looks quite different from eastern Jutland. The forests began advancing on the previously barren terrain which, at the time, still had a land connection to what we today know as England. And over the sandy terrain, hill islands rose as remnants of the last ice age and formed what we know as the modern landscape of western Jutland.

And then eventually humans migrated to the area. They fished for oysters and hunted now-extinct aurochs. The temperature increased, the ice continued melting, the seas rose metre by metre and the coasts eventually took on their modern shapes. And yet - because the sea is still hitting the shores, the temperatures are still changing and the sand is still slowly being moved by the wind. In the last 500 years, the sea has shifted the location of Holmlands Klit. A combination of sand, wind and human efforts have closed off the fjord which is now regulated by sluices and dikes, the salinity of the water has been lowered and the oysters have disappeared. Lakes have been turned into agricultural land. As with the local cuisine, the landscapes continue changing.

And then there is the power of humans to change the landscape. We are industrious and decisive when we put our minds to something. A stream is straightened and then later corrected back to its original course. Fjords and lakes are drained to create more agricultural land. And then agricultural land is allowed to flood to make room for the original natural landscape. Forests have been felled and used for fuel to make ores, for timber and for firewood. Heathlands have been preserved by grazing and in other places they have been turned into fields. A tradition of keeping cattle became a social movement, an entirely new way of organising agriculture as a community, and this has defined Danish food production ever since. There is an ability to get things done here.

There is ingenuity. Special new methods were found to deal with the local conditions. Fish were dried in the wind, smoke chests for meats were put by the fireplaces, products were made from the horns of the cattle that grazed in the landscapes. Ships were built without keels so that they could land directly on the beach of a coastline where there were no obvious port sites. Landscapes, decisiveness and a North Sea cuisine that is changing and has changed throughout the centuries.

Sheep among the dunes

Sheep are everywhere. On Skallingen, the heath and on dinner plates throughout history. Sheep thrive in areas with poor soil, on meadows and in the dunes. In the Danish city of Ho, there has been held sheep markets for centuries where wood and sheep herded directly from Skallingen were traded. With sheep being an important part of the entire local community, they have also assumed an important place in the local cuisine. Salted, smoked and dried mutton and lamb meat became significant parts of the diet. The dried lamb meat was preferred over the smoked lamb meat.

“No other creature fits so well into this landscape as sheep.”

Legs of lamb dried by the chimney were considered delicacies. The meat was used for sheep roll sausages, barbecued mutton and lamb and the cabbage was cooked on salted mutton. Mutton and lamb meatballs are also a recurring food, and in some homes they were preserved in jars of melted sheep’s tallow or fat. There are also descriptions of fluted sheep’s heads, fried on a grate over fire from heather peat. The same grate was used to fry herring. For special occasions, a whole goose, duck, hare or a lamb could also be fried over the fire on a roasting split. We also see lamb patties, lamb chops and racks of lamb featuring in old recipe books.

Photo:Thomas Høyrup Christensen

Fish in the west wind

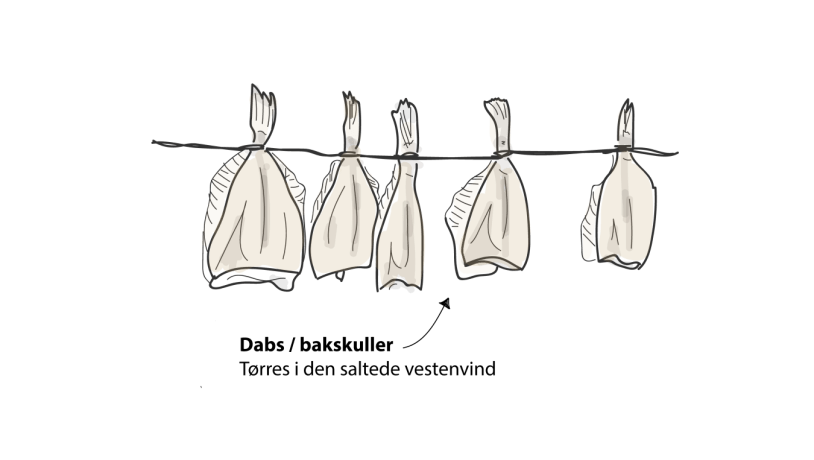

An indisputably distinctive feature of historic North Sea cuisine is the air-dried fish. The rough western winds were harnessed as a resource. In the historic kitchens, making food that could last was always a challenge, not least for fresh fish. Various types of processing could help lower the water content and thus also lower the risk of the food spoiling. Salting, smoking and drying were all methods that could reduce the liquid contents and extend shelf life, and often these techniques were used together. The western coast of Jutland has optimal conditions for drying food in the salty west wind. A special kind of air-drying craft developed here. If it was raining, the fish could be brought under a roof for a while.

The most famous are the dried flatfish, often dabs, which have been hanging in pairs on cords directly exposed to the west wind for centuries. At Hvide Sande the fish are called dabs, like in English, but further south they are called by a Danish name: “Bakskulder”. When the author Achton Friis stopped by Henne Kro in the early 1930s, he was served the golden brown “dried flounder” which was called “bakskulder” in this area. It was prepared directly laid down in the stove’s peat glows, wrapped in thick paper. When the paper burned off, it was taken up and served piping hot at both the breakfast and lunch table. It was sparkling in its own fats and served with a cool beer. He does not mention the rye bread, however, which the fish has often been served on through time. Some times the dabs was only dried, but most often, it was also smoked. This is one of the historical food traditions that is still seen today. In late spring, Hvide Sande has a “Dabsens Dag” (“Day of the Dabs”).

Photo:VisitVesterhavet

The dabs and other flatfish were far from the only fish that were processed directly in the wind. Rays, cod, whiting and haddock were also dried in the wind. As you get very close to the coasts, fish have generally been a huge part of the local diet. There were homes were one ate dried fish with the fresh fish instead of bread. It was written in 1890 that both rays and dogfish were frequently caught along the western coast of Jutland, often large quantities, and that they were a source of food for the local inhabitants. They were caught on the same hooks used for haddock and cod. In the old days, they were suspended on rods and left to dry. A document from a farm by Oksby also describes that they had large vats and wine anchors where the fish were salted and then dried in the large open space.

Seasonal fishing

In the old days, ships would sail in directly to the beach by the fishing villages that were often all the way out on the sea dunes. There was a lack of natural piers, and the shape of the coast made it difficult to build ports on the west coast. The boats for the small fishing villages were therefore built without keels, so they could glide more easily across the sand. It is clear that the majority of fishermen were seasonal fishermen. Spring fishing went from April to June and autumn fishing lasted from October and into the new year. It was rare to fish between midsummer’s eve (23 June) and Saint Mikkel’s day on 29 September. Instead, people worked on securing the harvest, as many were both farmers and fishermen, switching between the two. Here, coastal fishing and agriculture were adapted to the conditions of nature and the local resources.

Photo:VisitVesterhavet

During winters, there was processed reeds for thatched roofs and fished on the ice of the fjord. At Ringkøbing Fjord, there was also developed a special winter fishing method on the ice that involved cutting a t-shaped hole in the ice in one location and then cutting a round hole further away A special kind of plunger was used to ‘pulse’ or pump the hole while another tool with a brace and a net was pulled through the t-shaped hole in the ice simultaneously. This method caught flatfish in the net. Perhaps it was the so-called ‘stadelflyndre’ (‘Stadil flounders’) from Stadil Fjord that were referred to in 1777 as ‘beautiful’.

The fishing techniques varied from place to place. The small fishing villages were spread along the coast down to Skallingen. Tipper Fiskerleje, which is today a peninsula inside Ringkøbing Fjord, was right by the coast before the fjord closed and a toll had to be paid in cod. At Klithane and Nyminde, the toll was paid in whiting. Further south, by Tudal, Tudhul, Uldal and Vesterside, the toll was paid in flatfish. This is consistent with the fact that fishing for plaice and flatfish in general was very popular in the seas of Skallingen. South of Ringkøbing Fjord there was created salting houses for whiting and cod. Further south, close to Oksby, there was also created a large salting house. Whether it was flatfish or cod fish, the dried and salted fish, with their long shelf life, were well suited to trade. Through this trade, the coastal people and farmers from the inland were in contact on an ongoing basis.

Hunting the fjords and foraging in the dunes

In addition to the exchange of goods between the coastal peoples and the farmers, many peoples in the coastal regions have probably had some kind of mixed economy of seasonal fishing, sheep farming, hunting and foraging. Bird eggs were collected and, among other things, many sea gull eggs were eaten. Hares were also caught and wild birds were frequent targets for hunters. Ducks and snipes. We know from a cookbook from 1814 belonging to the local bourgeoisie in Ringkøbing that wild game was also a popular food. The cookbook has recipes for hares, different types of deer and venison racks and haunches.

Photo:VisitVesterhavet

It was particularly by the western Jutland fjords that there was a lot of hunting - and the now illegal barrel hunting of ducks was widespread. The shooting barrels were constructed to suit the shallow and calm waters of the fjords. A shooting barrel consisted of an exterior barrel buried into the bottom of the fjord with openings at the top and bottom. There was another barrel inside with a fixed bottom attached to the outer barrel with chains that could be adjusted to fit the tide. The shooting barrels were used in Ringkøbing Fjord and other places up until 1967 when it was made illegal. Barrel hunting was particularly used to hunt for teal ducks, Eurasian wigeons, gadwalls and mallards.

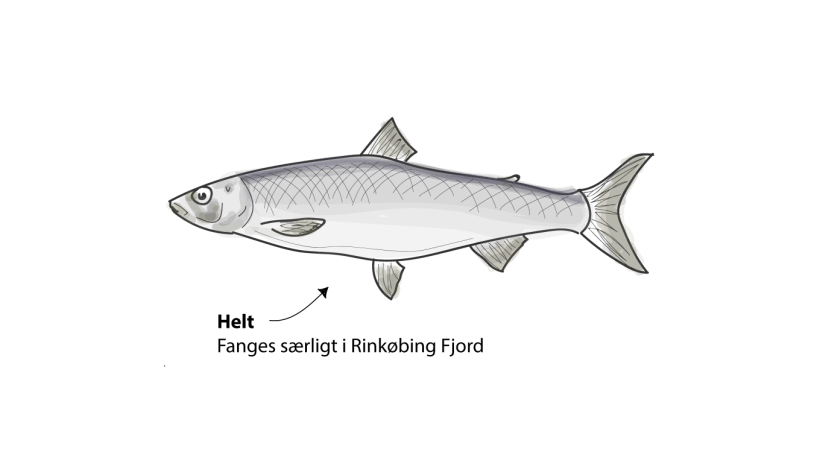

Oysters, salmon, common whitefish, perches and pikes

Before Holmlands Klit migrated south and closed the salty sea water, there were also oysters in Ringkøbing Fjord. Even at the beginning of the 1700s, the fjord was so open and salty that the Royal Danish oyster catch was still leased out. At the time, oysters were a royal privilege and it required a permit to fish for them. We do not know much about how they were consumed in the area at the time, but we do know that oysters were shipped off in barrels to dukes and royals elsewhere in Northern Europe. It was a valuable industry. However, as the salinity levels fell during the 1700s and made life difficult for oysters, it provided opportunities for new species. The freshwater and brackish water fish took over. On a fishing map from 1890, it is clear that what was now Denmark’s largest inland sea, Ringkøbing Fjord, had one of the country’s most important perch and pike fisheries. Fish traps and fyke nets were used to catch the fish. Eels were also caught in fyke nets in 1890 in Ringkøbing Fjord, while salmon was caught using both nets, fish traps and fyke nets.

They were also still caught using ‘fish farms’ in the large streams, which were a highly advanced method of catching fish. In 1890, there was still a ‘salmon fish farm’ in Skjern Å, and fish farms were impressive structures. They were a kind of giant fyke net using a woodwork built across the stream structured as a giant enclosure with the tips against the stream. The construction of these required a lot of knowledge about how the fish moved. Once the salmon was caught in the trap, a lid could be opened up behind it using rope from the fisherman’s catch tower. There were also ‘salmon farms’ in Varde Å. In general, the fisheries in the streams of western Jutland were very impressive. In 1777, it is mentioned that there was ‘exceptional fishing’ of salmon, trout, graylings and common whitefish.

Photo:VisitVesterhavet

It is particularly the common white fish has a special connection to the local area. It is not known in many places in the country other than the west coast of Jutland and parts of Limfjorden. It is a type of salmon that thrives in brackish waters such as those in Ringkøbing Fjord. It has been eaten over centuries in the area, both boiled, salted, fried and particularly smoked. Even in the 1970s and 80s, it is described that you could get smoked common whitefish at virtually every restaurant in Ringkøbing, both at the fine dining restaurants and the more modest restaurants. At the fine dining establishments, it was a major component of the cold buffet tables, cut into pieces and then re-assembled on a so-called ‘sand dune’ made from salt. Toothpicks were used to elevate the head and tail. It was also often served on a few slices of rye bread.

At Varde, there was a particular historical method of preparing salmon. Once it had been cleaned, it was laid down in its own blood and then smoked in a barrel. It is described that nettles and alder resulted in the best smoking of the salmon, and they were then purchased by rich merchants and shipped to Hamburg. At the outlet of Varde Å, many salmon were caught when, at spring and summer time, the fish migrated up through Ho Bugten from the sea. The salted and smoked Varde salmon was generally famous for its fine quality.

Kitchen tools of western Jutland

As can be seen, the North Sea cuisine is based on the natural conditions of the area. The salty wind was used to develop a craft that dried fish out in the open. Fisheries have adapted to changing salinity levels and a stretch of coastline that was characterised by sand, storms and shifting dunes. However, a food culture is shaped by more than just the conditions of nature and it is about more than the produce used and the preparation techniques. The kitchen tools themselves, pots, pans, smoke chests and roasting grates all impact the regional flavour of foods. The kitchenware used shapes the cooking options, and in some cases also directly influence the taste of what you are making. This also applied to the western Jutland ‘Jutland pots’, which is one of Denmark’s oldest cooking crafts used in the region between Ølgod and Varde.

The Varde pots were in high demand in German and Dutch cities precisely because of their cooking qualities. They did not burn the food and they did not leave an aftertaste like other pots did - and it was also said that meats and fats cooked in these pots lasted longer. This is because the quality of the local clay varied greatly from place to place. The Jutland pots were made from the blue clay of the local area. The blue clay was dug up during the autumn and then left over the winter to either become tender or brittle. In March the clay was then kneaded, first with the feet and then with the hands. The finished Jutland pots were then covered with chalky water and polished to a shiny finish with a stone and sometimes ornamented. The Jutland pots were first burned over glowing heather peat in a recessed stone oven and then covered by heather peat over an open flame. The dark colour of the smoke was thus preserved in the pots, which has probably helped give them the qualities that were coveted further south.

Sætkag is a historic western and south-western Jutland dish, named after the set it was baked in. It was a milk platter in which the milk was stored until the cream settled. In this area, the milk platter was made from clay and had a black colour. The ‘sætkage’ is an oven kage which is also known further south along the Wadden Sea islands. Slices of pork were placed at the bottom and a bit up to the sides and then a dough of milk and barley flour (later also wheat flour) was poured into the platter and then more slices of pork were added on top. This is not to be confused with ‘satkuk’ or ‘sakuk’, which is a flour pudding that was also eaten in the area with pork, syrup and potatoes and sometimes gravy instead of syrup. The satkuk was made in a homemade bag until the pudding form became more popular in the late 1800s. In an old recipe from Ringkøbing it was also made with currants, raisins and a bit of nutmeg. A similar dish with a similar name is also known from Fanø. The western Jutland tradition of horn goods - spoons and other cookware developed from cattle horns - is rooted in the produce traditions of the area. Cattle has also been a key part of western Jutland’s culinary history.

Steer farming

Sand is a major feature of the landscapes of western Jutland. It is found both on the beach, in the dunes and in the soil. Ever since the ice age meltwater rivers washed out the soils, there has been a lack of nutrient soils here. The heather peat's subsiding humic acids further contributed to the degradation of the nutrient salts. Fortunately, there were solutions. If grains are to grow in such areas they require fertiliser, and cattle could help with this - but cattle require grass and grass requires meadows. The meadows were the main source of food for western Jutland, they provided a basis for subsistence and they provided grazing for cattle and hay for the winter. This is why all of the manors in western Jutland were built by streams or fjords - this is where the meadows and fertile grasslands were. It is a characteristic of the historic western Jutland cattle that their fodder has been linked almost exclusively to the meadows. The areas in western Jutland were very suitable for cattle farming. Besides the soil conditions, there were large sparsely populated steppes that were easier to use for cattle grazing than agriculture. Grain cultivation also required a larger workforce than steer or sheep farming, which could be done with just a shepherd roaming the landscape.

It must have been an incredible sight to have seen the large steer herds wandering through the landscapes from 1500-1700. They could be either heading for a boat to sell the live cattle at the cattle markets to the south or they could be walking on land directly to these markets in large herds. Back then, people preferred the castrated bull calves, the steers, simply because of their tasty meat. The steers had a tendency to gain weight, and this made for fattier and tastier meat. The export of steers was critical for Danish prosperity throughout these centuries. The export brought in foreign currency that could be used to buy, for example, salt, which had an absolutely critical role in extending the shelf life of other produce. And here, the western Jutland steers had a particular advantage. A text from 1777 states that ‘the Jutland steers surpass the steers of all other provinces because the juiciness of the meat and the fineness of the threads are particularly well-suited to be permeated by the salt.’ The impact of selling steers has been huge. Ringkøbing’s emergence as a maritime trading city is due, among other things, to steer exports in the High Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Even if steer farming went back centuries, it was the long western Jutland tradition of cattle farming that was the reason for this area in particular resulting in a critical innovation - an innovation that would change Danish agriculture, food production and prosperity ever since.

The world’s first cooperative dairy

Hjedding Andelsmejeri can be found a little bit outside of Ølgod (‘andelsmejeri’ means ‘cooperative dairy’ in English). Today, it is a museum for the memory of the world’s first cooperative dairy which appeared in this very spot. In subsequent years, cooperative dairies sprung up all over Denmark and just 12 years later than were 907 such enterprises across Denmark. And the fact that it started here is no coincidence. A number of factors played a key role, among them, the local traditions of cattle farming and the proximity to England, the most important export market for Danish butter. That railroads were being built in this time only helped speed things along further. In those years, Danish agriculture went through a completely wild reshuffling. Profitable grain sales had come to an abrupt end, the grain prices plummeted and this created a worldwide crisis. Whether it was these familiar challenging conditions that once again favoured the toughness of the people of western Jutland is up for debate. But the idea of making the dairy producers co-owners of the dairy was a groundbreaking idea, as it put them higher up in the value chain and made them united and stronger together. Previously, dairies had mainly been concentrated at the manors, as small farmers did not have enough cattle to really produce dairy at scale. However, now that they were organising themselves into a cooperative, things looked very different. With their co-ownership of dairies, they also had greater obligations to ensure the highest quality of the milk.

Buttermilk and gooseberries

With the tradition of cattle breeding, it is also perhaps not surprising that we are rediscovering a lot of historical buttermilk recipes in the area. There are barley groats cooked in buttermilk for sour porridge. Buttermilk bread soup, raw buttermilk soup, buttermilk dessert and cold buttermilk soup are all recurring in the old handwritten recipe booklets. Besides the buttermilk, sheep and dried fish, the gooseberries are also conspicuous in the western Jutland recipes. They were growing in the western Jutland gardens, and it was precisely the austerity of the gooseberries that also made them suitable for the area's climate. They were used for compote and jelly.

Photo:VisitVesterhavet

A little further north in the western Jutland regions there are descriptions of gooseberry pork with apple or pear pork recipes. The gooseberries are mentioned from the start of the 1800, which is the date of the oldest recipes. There was made gooseberry juice, gooseberry jam, gooseberry porridge and gooseberries for roasting. Green gooseberries were also picked in a thick juice. The natural conditions of western Jutland can be considered both as a challenge and a resource. Regardless, however, the natural conditions have shaped the historical food culture. The wind has dried the fish, the clay and heather have shaped the kitchenware, the dunes and heathlands have looked after the sheep and the cattle have thrived in the wide open landscapes. Traditions passed on through the centuries created prosperity and a basis for further development. These were all things that helped to shape the current society of western Jutland and the taste of the North Sea cuisine. And then we have not even mentioned how potatoes have thrived on the sandy fields of western Jutland.